This article is a repost of a paper written by Julia Tanenbaum and published by pglavin16 on October 26, 2016. It's still accessible in Institute for Anarchist Studies' archive

To Destroy Domination in All Its Forms: Anarcha-Feminist Theory, Organization and Action 1970-1978, by Julia Tanenbaum

As anarchists look for genealogies of principles and praxis in a variety of social movements, from the anarcho-pacifists who spoke out against World War II to anarchists who joined the Black Power movement, so too should they look for their feminist foremothers, not only in the early 20th century anarchist movement but in the radical women’s movement of the 1970s. Many radical feminists shared anarchist goals such as ending domination, hierarchy, capitalism, gender roles, and interpersonal violence, and utilized and influenced the key anarchist organizational structure of the small leaderless affinity group. They grappled with the questions of how to balance autonomy and egalitarianism and create nonhierarchical organizations that also promoted personal growth and leadership. In 1974 Lynne Farrow wrote, “Feminism practices what anarchism preaches[1].”

Anarcha-feminism was at first created and defined by women who saw radical feminism itself as anarchistic. In 1970, during the rapid growth of small leaderless consciousness raising (CR) groups around the country, and a corresponding theory of radical feminism that opposed domination, some feminists, usually after discovering anarchism through the writings of Emma Goldman, observed the “intuitive anarchism” of the women’s liberation movement. Radical feminism emphasized the personal as political, what we would now call prefigurative politics, and a dedication to ending hierarchy and domination, both in theory and practice.2 CR groups functioned as the central organizational form of the radical feminist movement, and by extension the early anarcha-feminist movement. 3 Members shared their feelings and experiences and realized that their problems were political. The theories of patriarchy they developed explained what women initially saw as personal failures. Consciousness raising was not therapy, as liberal feminists and politicos frequently claimed; its purpose was social transformation not self-transformation.4 Radical feminist and anarchist theory and practice share remarkable similarities. In a 1972 article critiquing Rita Mae Brown’s calls for a lesbian party, anarchist working-class lesbian feminist Su Katz described how her anarchism came “directly out of” her feminism, and meant decentralization, teaching women to take care of one another, and smashing power relations, all of which were feminist values.5 Radical feminism attributed domination to the nuclear family structure, which they claimed treats children and women as property and teaches them to obey authority in all aspects of life, and to patriarchal hierarchical thought patterns that encouraged relationships of dominance and submission.6 To radical feminists and anarcha-feminists, the alternative to domination was sisterhood, which would replace hierarchy and the nuclear family with relationships based on autonomy and equality. A chant that appeared in a 1970 issue of a feminist newspaper read “We learn the joys of equality/Of relationships without dominance/Among sisters/We destroy domination in all its forms.”7 These relationships, structured around sisterhood, trust, and friendship, were of particular importance to the radical feminist vision of abolishing hierarchy. As radical feminist theologian Mary Daly wrote in 1973, “The development of sisterhood is a unique threat, for it is directed against the basic social and psychic model of hierarchy and domination.”8 Radical feminists opposed the “male domineering attitude” and “male hierarchical thought patterns,” and attempted to act as equals in relationships deeper than male friendships.9

To feminists familiar with anarchism, the connections between both radical feminist and anarchist theory and practice were obvious. Anarchist feminism was essentially a step in self-conscious theoretical development, and anarcha-feminists believed that an explicit anarchist analysis, and knowledge of the history of anarchists who faced similar structural and theoretical obstacles, would help women overcome the coercion of elites and create groups structured to be accountable to their members but not hierarchical.10 They built an independent women’s movement and a feminist critique of anarchism, along with an anarchist critique of feminism. To anarcha-feminists, the women’s movement represented a new potential for anarchist revolution, for a movement to confront forms of domination and hierarchy, personal and political. Unlike Goldman, Voltaraine De Cleyre, the members of Mujeres Libres, and countless other female anarchists concerned with the status of women in the 19th and early 20th century, they became feminists before they became anarchists. Anarcha-feminists eventually merged into the anti-nuclear movement by the end of 1978, but not before contributing to crucial movement debates among both anarchists and feminists, building egalitarian, leaderless, and empowering alternative institutions, and altering US anarchism in theory and practice.

A. Becoming Anarcha-Feminists

The term “anarchist-feminist,” later used interchangeably with anarcho-feminism and anarcha-feminism, first appeared in an August 1970 issue of the Berkeley-based movement newspaper, It Ain’t Me Babe. The newspaper published an editorial calling for “feminist anarchist revolution” next to an article about Emma Goldman. The collective did not synthesize a theory of anarcha-feminism, but rather explained how their anarchist beliefs related to the organizational structure of the paper, which they designed as an affinity group to encourage autonomy and discourage “power relationships or leader follower patterns.”11It Ain’t Me Babe exemplified the “intuitive anarchism” of the early women’s liberation movement. It’s masthead read “end all hierarchies” and the paper contained articles like Ellen Leo’s “Power Trips,” which exemplified the radical feminist tendency to oppose all forms of domination. Leo wrote in 1970, “The oppression of women is not an isolated phenomenon. It is but one of the many forms of domination in this society. It is a basic belief that one person or group of people has the right to subjugate, rule and boss others.”12 Like anarchists, these feminists connected the oppression of women to a larger phenomenon of domination. Beginning in 1968 and growing in strength until 1972, radical feminism was anything but monolithic and many participants differed greatly in regards to their views on sexuality, the family, the state, organizational structure, and the inclusion of transgender women in the movement.

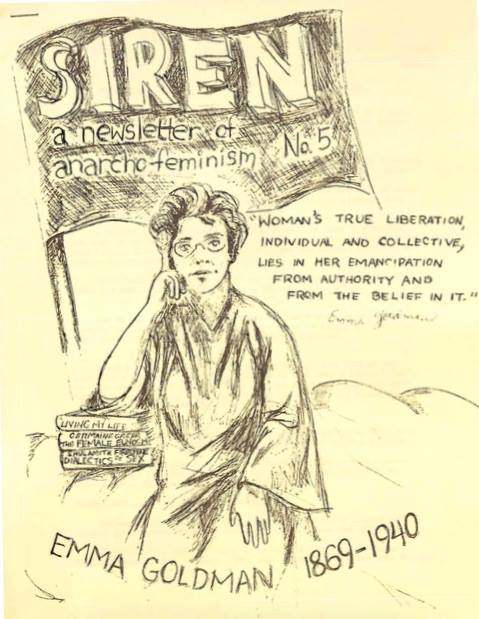

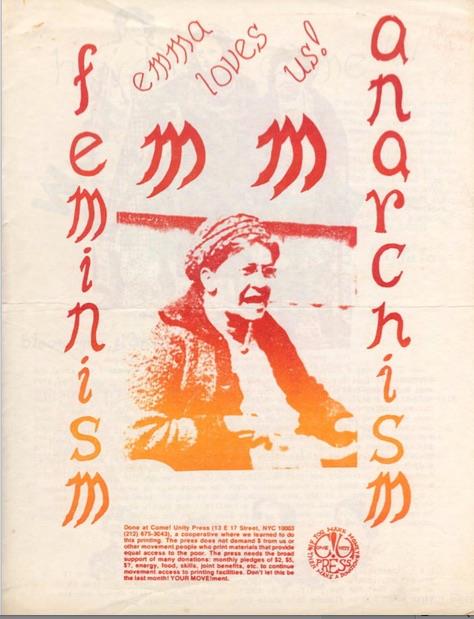

Most anarcha-feminists were initially radicalized by the political and cultural milieu of the anti-war movement, but it was their experiences in the women’s liberation movement combined with the influence of Emma Goldman that led them to develop anarcha-feminism as a strategy. As feminists struggled to reclaim women’s history, Goldman became a feminist icon due to her advocacy of birth control, free love, and personal freedom. In 1971 radical feminist novelist and historian Alix Kates Shulman wrote, “Emma Goldman’s name has re-emerged from obscurity to become a veritable password of radical feminism. Her works rose from the limbo of being out of print to…being available in paperback. Her face began appearing on T-shirts, her name on posters, her words on banners.”13 Goldman criticized the bourgeois feminist movement and its goal of suffrage, which led many women to criticize her as a “man’s woman.” However, Shulman and many others argued that Goldman was a radical feminist worthy of recognition because she stressed the oppression of women as women by the institutions of the patriarchal family and puritan morality, as well as religion and the state.14 As anarcha-feminist Cathy Levine wrote in 1974, “The style, the audacity of Emma Goldman, has been touted by women who do not regard themselves as anarchists… because Emma was so right-on…. It is no accident, either, that the anarchist Red Terror named Emma was also an advocate and practitioner of free-love; she was an affront to more capitalist shackles than any of her Marxist contemporaries.”15 Feminists honored Goldman’s ideas and legacy by opening an Emma Goldman Clinic for Women in Iowa in 1973, publishing new volumes of her work, naming their theater troupes after her, and writing screenplays, operas, and stage plays about her life. 16 In 1970, the women’s liberation periodical Off Our Backs dedicated an issue to Goldman with her image on the cover. Despite this, Betsy Auleta and Bobbie Goldstone’s article about Goldman’s life discussed what they perceived as her faults (her opposition to suffrage and disconnect from much of the women’s movement) because she had become a “super-heroine” in the movement. 17

C. Siren and Early Anarcha-feminist Networks

Goldman encouraged women to make connections between radical feminism and anarchism, and her writings often served as radical feminists’ introduction to anarchism or the impetus for them to make connections between anarchism and feminism. To many anarcha-feminists this theory represented both a critique of the sexism of the male New Left, including its anarchist members, as well as a critique of socialist and liberal feminism. Despite this intuitive anarchism, attempts by early anarcha-feminists to develop an anarchist analysis within many radical feminist collectives felt silenced, while women in the anarchist movement, where misogyny ruled as much as in the rest of the New Left, also felt alienated. Anarcho-feminist attempts to elucidate connections between feminism and anarchism, like those of Arlene Meyers and Evan Paxton, were often met with intimidation and censorship in mixed groups. These conditions created the possibility for an independent anarcha-feminist movement, but first, anarcha-feminists would have to communicate and develop their theories.

Goldman encouraged women to make connections between radical feminism and anarchism, and her writings often served as radical feminists’ introduction to anarchism or the impetus for them to make connections between anarchism and feminism. To many anarcha-feminists this theory represented both a critique of the sexism of the male New Left, including its anarchist members, as well as a critique of socialist and liberal feminism. Despite this intuitive anarchism, attempts by early anarcha-feminists to develop an anarchist analysis within many radical feminist collectives felt silenced, while women in the anarchist movement, where misogyny ruled as much as in the rest of the New Left, also felt alienated. Anarcho-feminist attempts to elucidate connections between feminism and anarchism, like those of Arlene Meyers and Evan Paxton, were often met with intimidation and censorship in mixed groups. These conditions created the possibility for an independent anarcha-feminist movement, but first, anarcha-feminists would have to communicate and develop their theories.

Early anarcha-feminist theory and debate emerged through Siren newsletter. The first issue, produced as a journal in 1971, contained “Who We Are: The Anarcho-Feminist Manifesto,” written by Arlene Wilson, a member of the Chicago Anarcho-Feminist Collective.18 The manifesto focused on differentiating anarcha-feminism from socialist feminism through a critique of the state: “The intelligence of womankind has at last been brought to bear on such oppressive male inventions as the church and the legal family; it must now be brought to re-evaluate the ultimate stronghold of male domination, the State.”19

In February of 1970 Arlene Meyers and the Siren collective switched from journal to newsletter format, which allowed feminists throughout the US to participate in defining anarcha-feminism and its theory.20 Siren allowed women in diverse (often not explicitly anarchist) collectives in many regions of the country to communicate and develop their theory. Later issues of the newsletter included news items related to feminist and anarchist activism, including political prisoner support for anarchists in Spain through the Anarchist Black Cross, women’s health clinics, childcare and living collectives, and working at infoshops like Mother Earth Bookstore.21

The last three issues of Siren, published in 1973, contain the majority of the newsletter’s analysis and debate, covering topics such as state power and authoritarianism, prefigurative politics, lesbian feminism, and gender identity and expression. Issue 10 of Siren contained two statements by transgender individuals, critiquing both sexism and the gender binary, and offering a progressive vision of transgender inclusion within the movement. Eden W, a member of the Tucson Anarcho-Feminists, described her experiences as a “male woman” and critiqued “the authoritarianism that demands that males must be of one gender and females of another,” thus critiquing the gender binary itself as a form of authoritarianism..22 Finally, she asked feminists to look on “femmiphiles” as their sisters.23

This essay stood in contrast with the prejudice towards trans women in the larger radical feminist movement, which sometimes portrayed them as interlopers who brought male privilege into women only spaces. That same year radical feminist Robin Morgan famously denounced male to female transgender feminist songwriter and activist Beth Elliot as a rapist and “infiltrator” at the 1973 West Coast Lesbian Conference, although it is worth noting that two-thirds of the conference-goers voted for Elliot to stay.24 Some feminists conflated transgender women with men in drag, accused them of being rapists, and felt that they retained male privilege and should not be allowed in feminist spaces.25 Although anarcha-feminists were undoubtedly influenced by this discourse, attitudes towards transgender people were not monolithic in the feminist movement at large. Eden W’s statement emphasizes that she is heterosexual, perhaps because of this widespread fear of transgender women as rapist infiltrators. This limited discussion of transsexuality nevertheless reveals that anarcha-feminists were willing to discuss this conflict, and give transgender people a voice in the movement.

Issue 8 of Siren also contained “Blood of the Flower,” a statement written by Marian Leighton and Cathy Levine, members of the Cambridge based Black Rose Anarcho-Feminist collective.26 Unlike Wilson, Leighton and Levine reject not only socialist feminism’s analysis of the state, but its tactics and the idea of movement building altogether. To them, “movements,” as represented by the male Left and its ideas of a vanguard, separated politics from personal dreams of liberation until women abandoned their dreams or dropped out of the movement altogether. Instead, they advocated leaderless affinity groups in which each member could act as an individual, and presented this anarchist form of organization as the alternative to hierarchical movement politics practiced by socialist feminists and liberal feminists. The small leaderless affinity group allows members to participate “on an equal level of power” without leadership determining the direction of the movement.27 They wrote, “Organizing women, in the New Left and Marxist left, is viewed as amassing troops for the Revolution. But we affirm that each woman joining in struggle is the Revolution.”28 This anarcha-feminist vision, almost similar to the cell-like structure of earlier insurrectionary anarchist groups, emphasized valuing individual contributions in small groups instead of building the large, often authoritarian, and impersonal “revolutionary armies” that many New Leftists and socialist feminists envisioned. To achieve this, anarcha-feminists would build their movement through small affinity groups and participating in various feminist and anarchist counter-institutions.

D. Small Groups, Growing Networks

Anarcha-feminists also formed study groups, which, like the CR groups, also acted as affinity groups, and formed and dissolved quickly. Many groups were located in university towns, partially due to the success of AnarchoFeminist Network Notes as a communications network, which allowed activists to communicate and organize outside of major urban areas. Collectives were often small, flexible, and project based. Because they required intimacy and small size, when groups became too large, as the Des Moines and Cambridge based Black Rose Anarcho-Feminists did, they split into multiple study and action groups.29 These groups also acted as affinity groups that collectively participated in action around various local and national issues, from the local food coop to international political prisoner support to the lesbian movement to ecology struggles and the anti-nuclear movement.30

Anarcha-feminists also formed study groups, which, like the CR groups, also acted as affinity groups, and formed and dissolved quickly. Many groups were located in university towns, partially due to the success of AnarchoFeminist Network Notes as a communications network, which allowed activists to communicate and organize outside of major urban areas. Collectives were often small, flexible, and project based. Because they required intimacy and small size, when groups became too large, as the Des Moines and Cambridge based Black Rose Anarcho-Feminists did, they split into multiple study and action groups.29 These groups also acted as affinity groups that collectively participated in action around various local and national issues, from the local food coop to international political prisoner support to the lesbian movement to ecology struggles and the anti-nuclear movement.30

The collective Tiamat originated in Ithaca, New York in 1975 and dissolved in 1978. Their name originated from the tale of a goddess of chaos and creation, feared by men but worshiped by women.31 The collective read anarchist theory together, shared ideas, and put out an issue of the newsletter Anarcha-Feminist Notes in 1977. According to former member Elaine Leeder’s reflections, the collective members participated in political activities ranging from protesting the building of a local shopping mall to raising money for a day care center for political dissidents in Chile. Furthermore, Leeder argued that the collective was a functioning “anarchistic society”: “We are leaderless, non-hierarchical… and always ready to change. We live self-management, learn what it is together…and support each other.” 32 Tiamat supported Leeder’s interest in the mental health liberation movement and her successful effort to stop the introduction of electro-shock therapy at a local mental hospital.33

Anarcha-feminists worked in a wide variety of movements, and thus brought their prefigurative and feminist ideas to a diverse audience. Furthermore, a focus on education allowed anarcha-feminists to develop their own autonomy and talents. However, these diverse activities and the ephemeral nature of these collectives illustrate why anarcha-feminism is almost always ignored by historians and documents or records of these collectives are difficult to find.

To unite a small, decentralized movement, anarcha-feminists created communications networks through newsletters and conferences. At the Yellow Springs Socialist Feminist Conference in Ohio in 1975, the future members of Tiamat met and anarcha-feminists proposed that they should combine their networks and mailing lists.34 After the conference, anarcha-feminists established new collectives in Bloomington, Illinois, and Buffalo, New York.35 The conference was considered notable for its lack of a definitive definition of socialist feminism, and its broad “principles of unity” included two items associated with radical feminism and anarcha-feminism, but condemned by male socialists: recognizing the need for an autonomous women’s movement, and that all oppression is interrelated.36 Its broad principles illustrated how socialist feminists viewed economic oppression as one of many forms of domination rather than as the “lynchpin,” as male Marxists tended to argue.

Similar in format to Siren, Anarcha-Feminist Notes originated from a merger of two short-lived newsletters, Anarcho-Feminist Network Notes and The Anarchist-Feminist Communications Network.37 A different collective published each issue of the newsletter, and thus each varied in style and content. The Des Moines anarcha-feminist study and action group, Tiamat, and the Utopian Feminists were among the collectives who published issues of the newsletter. Although the last issue was published in March 1978, Anarcha-Feminist Notes, while it existed, acted as an effective means of communication for a decentralized movement.

Prior to Tiamat’s dissolution, it sponsored an Anarcha-Feminist Conference in June 1978 that attracted women from London, Italy, Toronto, and several US cities.38 In an idyllic location in Ithaca, women attended three days of workshops on topics such as anarcha-feminism and unions, self-liberation as social change, the ecology movement and anarcha-feminism, women and violence, building the anarcha-feminist network, matriarchy and feminist spirituality, beards and body hair, combatting racism, and anarcha-feminism and class.39 The conference’s theme was “Anarcha-Feminism: Growing Stronger,” which referenced the growth of anarcha-feminist theory and action since its inception. A packet given to conference attendees contained an essay called Tribes by Martha Courtot, which echoed conference goers’ feelings about building anarcha-feminist community. “We tell you this: we are doing the impossible. We are teaching ourselves to be human. When we are finished, the strands which connect us will be unbreakable; already we are stronger than we ever have been.”40 Unlike purely cultural feminism, anarcha-feminists connected this strength and community to a larger fight against domination. Both their personal lives and organizing efforts in mixed movements like the ecology movement were important parts of their politics.

E. From Conscioussness Raising to Counter-Institutions

Historian Barbara Ryan argues that the “small group sector” of the feminist movement virtually disappeared by the mid ‘70s, due to ideological and practical conflicts within the movement and the influence of liberal feminists, who advocated larger structured organizations.41 However this frequent narrative, which emphasizes the fast rise and fall of small CR groups, negates the crucial contributions of anarcha-feminists, who continued to organize within small, decentralized, and leaderless feminist collectives throughout the 1970s. Radical feminists extended the CR group’s anarchistic structure to a variety of other projects, such as domestic violence shelters, living collectives, and periodicals, many of which continued to support women through the late 1970s and into the 1980s. According to Helen Ellenbogen’s 1977 review of anarcha-feminist groups, many of these collectives were not explicitly anarchist but “intuitively anarchist,” such as the grassroots domestic violence shelters in Cambridge and Los Angeles where anarcha-feminists worked and observed practices like discouraging women from calling the police to deal with abusive males.42 Ellenbogen remarks on how anarcha-feminists joined women’s health clinics in Los Angeles, Seattle, and Boston, which resisted cooperation with the state and utilized collective process.43 In a 1972 article in Siren, Los Angeles anarcha-feminist Evan Paxton explained the anarcha-feminist principles of these self-help clinics, including the one where she worked. Clinics gave “women the confidence and knowledge to take care of their own bodies, which is essential in the struggle for self control.”44 Women’s health clinics helped women avoid the paternalism of (usually male) doctors and gain self-control.45

Anarcha-feminists operated a free school in Baltimore, which taught courses on Wilhelm Reich, movement structural skills, how to form a co-op, and anarchist and feminist political theory.46 Others worked on media projects like feminist newspapers or journals such as Through the Looking Glass, which focused on women prisoners, The Second Wave, and feminist radio stations.47 This focus on outreach and education illustrates anarcha-feminists’ long-term approach to revolution. Theorists like Kornegger and Rebecca Staton argued that anarchist revolution, both historically and in the present, requires preparation through education, the creation of alternative non-hierarchical structures, changes in consciousness, and direct action.48 As Staton wrote in a 1975 article in Anarcho-Feminist Network Notes, “Anarchists…have seen their own role in the revolutionary process as agitators and educators—not as vanguard…. The Revolution, for Anarchists, is the transformation of society by people taking direct control of their own lives.”49 In 1976, in the first issue of Anarcha-Feminist Notes, Judi Stein, an anarcha-feminist who worked at a feminist health center, described her experiences with collective processes, self-help, and feminism there as “ways to live out anarchism.”50 By working at self-help clinics, free schools, feminist radio stations, newspapers, and domestic violence shelters, anarcha-feminists spread their ideas and organizational methods, and helped themselves and other women in their own struggles for autonomy.

Anarcha-feminists operated a free school in Baltimore, which taught courses on Wilhelm Reich, movement structural skills, how to form a co-op, and anarchist and feminist political theory.46 Others worked on media projects like feminist newspapers or journals such as Through the Looking Glass, which focused on women prisoners, The Second Wave, and feminist radio stations.47 This focus on outreach and education illustrates anarcha-feminists’ long-term approach to revolution. Theorists like Kornegger and Rebecca Staton argued that anarchist revolution, both historically and in the present, requires preparation through education, the creation of alternative non-hierarchical structures, changes in consciousness, and direct action.48 As Staton wrote in a 1975 article in Anarcho-Feminist Network Notes, “Anarchists…have seen their own role in the revolutionary process as agitators and educators—not as vanguard…. The Revolution, for Anarchists, is the transformation of society by people taking direct control of their own lives.”49 In 1976, in the first issue of Anarcha-Feminist Notes, Judi Stein, an anarcha-feminist who worked at a feminist health center, described her experiences with collective processes, self-help, and feminism there as “ways to live out anarchism.”50 By working at self-help clinics, free schools, feminist radio stations, newspapers, and domestic violence shelters, anarcha-feminists spread their ideas and organizational methods, and helped themselves and other women in their own struggles for autonomy.

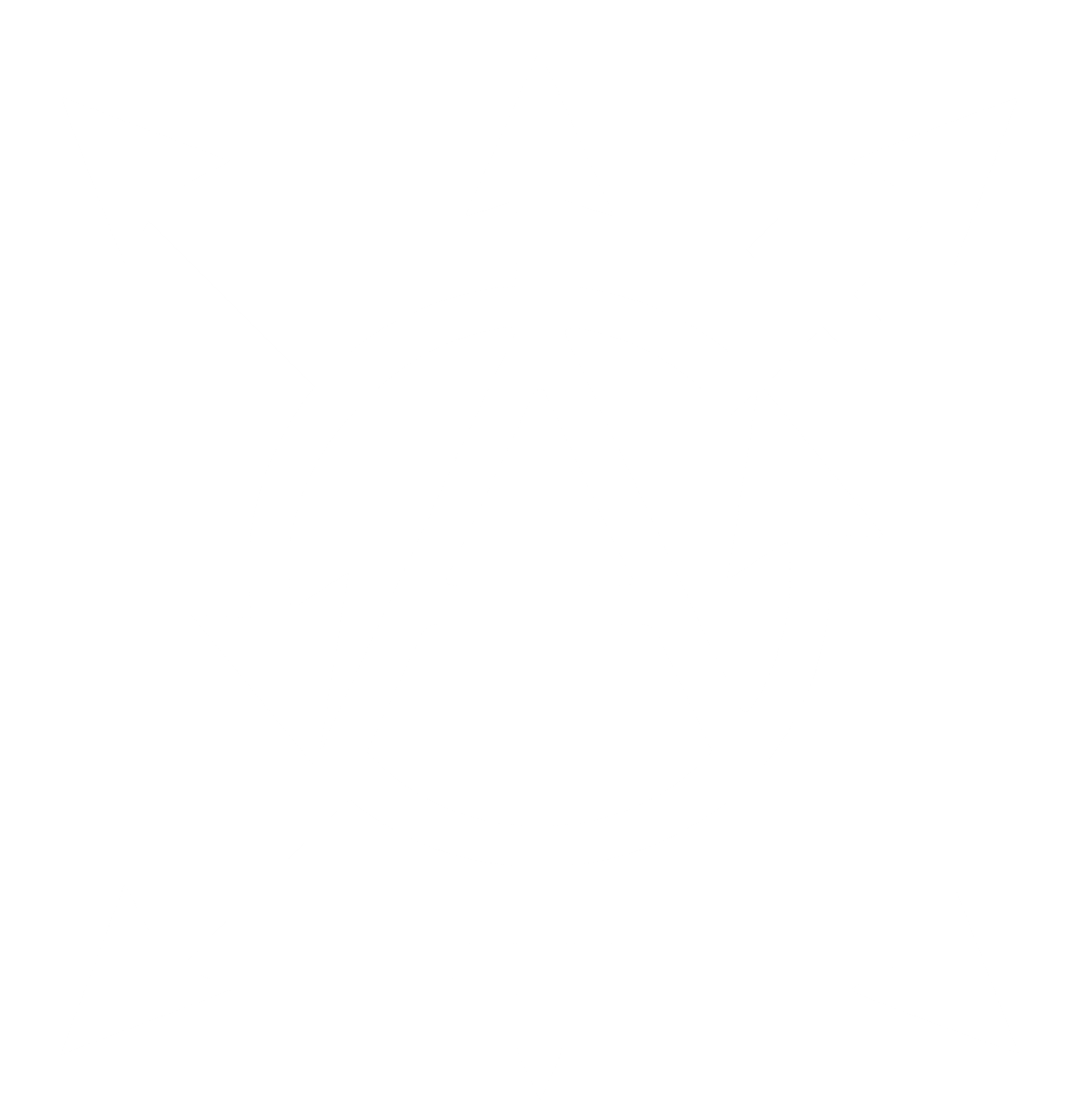

The self-described gay anarcho-feminist printer Come! Unity Press explicitly connected their political philosophy to their organizational structure. Founded in 1972, the press published Anarchism: The Feminist Connection, feminist writings of Emma Goldman, an issue of Anarcho-Feminist Notes, and other classic anarchist writings, like the speeches of Sacco and Vanzetti.51 Notably, they allowed members to decide for themselves how much they could afford to pay for the use of their printing facilities, which exemplified their anarcha-feminist philosophy of “survival by sharing.” The women of the press wrote in 1976, “As anarcho-feminists we want to end all forms of domination. Money is a…tool of power. It is a means of enforcing racism, sexism, or starvation and control over basic survival.”52 In a 1976 article critiquing “feminist businesses” in The Second Wave, Peggy Kornegger praised this model, and wrote that the press’ “‘survival by sharing’…certainly demonstrates if nothing else, that there are ways of confronting capitalism that don’t involve either power or control—and that work!”53 This alternative economic model helped the feminist movement, and its own members, survive.

F. “Anarcho-Sexism” and Anarcha-Feminist Interaction With the Anti-Capitalist Left

Anarcha-feminists also worked within the larger anarchist movement, attending anarchist conferences and confronting sexism in mixed groups. Anarcha-feminists attended the Anarchs of New York sponsored Live and Let Live Festival in April 1974. Anarcha-feminist groups like the New York Anarcho-Feminists and Come! Unity Press participated along with several hundred other conference goers, and the final schedule included four anarcha-feminist workshops amongst many other unscheduled lesbian and anarcha-feminist discussions and meet-ups. The feminist periodical Off Our Backs included a report on the conference written by two anarcha-feminists, Mecca Reliance and Jean Horan.54 Reliance, who attended both mixed and impromptu women-only workshops on anarcha-feminism, wrote that the mixed workshop was uninteresting and focused on the abolition of the nuclear family, apparently the only comfortable topic for the many male attendees, while the women-only workshop was energetic and facilitated a focus on organization and internal process.55 This mirrored one impetus towards separatism in the radical feminist movement: male dominated meetings in the New Left led women to censor their thoughts and long for an environment where they could speak freely and determine their own agenda.56Anarcha-feminists also attended the 1975 Midwest Anarchist Conference, and experienced several incidents of sexism, such as a man trying to take a hammer away from Karen Johnson, assuming that she could not use it because of her gender. However, the man eventually accepted her and other women’s criticism of his actions.57

Anarcha-feminists experienced sexism in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) meetings, and conflicts over sexism in anarchist periodicals like the Social Revolutionary Anarchist Federation Bulletin and The Match confirmed that many male anarchists shared the sexist attitudes of their Marxist counterparts.58 These attitudes encouraged separatism, but some anarcha-feminists worked in mixed collectives. Grant Purdy, a member of the Des Moines anarcha-feminist The New World Collective, which existed from 1973-76, wrote an article about her group’s experience in a mixed anarchist group called the Redwing Workers Organization (RWO) in the Spring 1977 issue of Anarcha-Feminist Notes.59 RWO focused on healthcare organizing, but the women in the group pushed feminist perspectives and led the group to treat personal struggles as political ones.60 She argued that despite frustrations, women could thrive in mixed groups if they created separate women’s groups outside of the larger organization, as the Des Moines women did. Women in mixed anarchist organizations taught male anarchists about their own misogyny and learned new skills from their comrades.61 However, for anarcha-feminists like Purdy, “involvement with men has always been conditional. Men are clear that they are not a priority for us over other women.”62 These separate women’s support groups and their presence at conferences illustrate how anarcha-feminists brought their ideas and organizational styles to the male anarchist movement as the radical feminist movement declined.

G. Differing Feminisms

From the beginning of the movement. anarcha-feminists differentiated socialist feminists and their theories from the traditional male socialist Left. In a 1971 article in the first issue of Siren, Arlene Wilson’s Chicago-based anarcha-feminist group emphasized that anarcho-feminists “are all socialists” and “refuse to give up this pre-Marxist term,” and continued, “We love our Marxist sisters…and have no interest in disassociating ourselves from their constructive struggles.” In 1974 Black Rose anarcha-feminist Marian Leighton commented that socialist feminist literature is not “narrowly dogmatic or opportunistic”63 like that of traditional male Marxists. Rather, it could be included in anarcha-feminist analysis. Anarcha-feminist film maker Lizzie Borden argued in a 1977 article in feminist art journal Heresies that Marxist women like Rosa Luxemburg, Alexandra Kollantai, and Angelica Balabanoff came closer to anarchism in their opposition to bureaucracy, authoritarianism, and the subversion of the revolution by the Bolsheviks than their male comrades.64 However, like Leighton, she emphasized that these anarchistic tendencies stemmed from socialization and lack of access to power, not simple essentialist understandings of gender. As Carol Ehrlich wrote in her 1977 article Socialism, Anarchism, and Feminism, which appealed to socialist and radical feminists to embrace anarchism, “Women of all classes, races, and life circumstances have been on the receiving end of domination too long to want to exchange one set of masters for another.”65 Leighton, Kronneger, and Ehrlich argued the defining distinction between radical feminism and anarcha-feminism was largely a step in self-conscious theoretical development.66 Thus, it was feminists’ unfamiliarity with anarchism that led them to embrace Marxism, although their ideology, “skeptical of any social theory that comes with a built-in set of leaders and followers” held more in common with anarchism.67

width="400">Anarcha-Feminists and socialist feminists often found their common interests outweighed their ideological differences, and worked together. Arlene Wilson was also a member of the socialist feminist group the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union (CWLU), along with other anti-authoritarian women.68 Wilson introduced Penny Pixler and other CWLU women to the Chicago chapter of the newly reconstituted IWW in the early 70s.69 They found the Chicago IWW less patriarchal and hierarchical than many Marxist parties and sects and were impressed with its history of women organizers. Several joined the union and became active in the Chicago Branch in addition to their continued work with CWLU projects.70 The CWLU dissolved acrimoniously in 1976 due to internal conflict over what some members observed as the group’s white middle-class orientation. Pixler and other former members shifted their primary activity to the IWW. Pixler contributed many articles to the Industrial Worker focusing on women workers, and contributed an article about the position of women in Maoist China to anarcha-feminist literary journal, Whirlwind in 1978.71

width="400">Anarcha-Feminists and socialist feminists often found their common interests outweighed their ideological differences, and worked together. Arlene Wilson was also a member of the socialist feminist group the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union (CWLU), along with other anti-authoritarian women.68 Wilson introduced Penny Pixler and other CWLU women to the Chicago chapter of the newly reconstituted IWW in the early 70s.69 They found the Chicago IWW less patriarchal and hierarchical than many Marxist parties and sects and were impressed with its history of women organizers. Several joined the union and became active in the Chicago Branch in addition to their continued work with CWLU projects.70 The CWLU dissolved acrimoniously in 1976 due to internal conflict over what some members observed as the group’s white middle-class orientation. Pixler and other former members shifted their primary activity to the IWW. Pixler contributed many articles to the Industrial Worker focusing on women workers, and contributed an article about the position of women in Maoist China to anarcha-feminist literary journal, Whirlwind in 1978.71

Anarcha-Feminists were also influenced by the theories of the French situationists, who positioned women’s oppression as a part of larger systems of power relations without reducing it to an effect of capitalism. Carol Ehrlich and Lynne Farrow argued that Situationism should be a component of anarcha-feminist analysis because it emphasizes both an awareness of capitalist oppression and the need to transform everyday life.72 Situationists expanded Marx’s theories of alienation and commodity fetishism to apply to modern consumer capitalism and argued that capitalist society led to the increasing tendency towards the consumption of social relations and identity through commodities and alienated people from all aspects of their lives, not just their labor.73 In her 1977 article Socialism, Anarchism, and Feminism, Ehrlich argued that a Situationist analysis is applicable to anarcha-feminist theory. With a Situationist analysis, all women’s oppression is real, despite their class status. Furthermore, women held a special relationship to the commodity economy as both consumers and objects to be consumed by men. Ehlrich argued “A Situationist analysis ties consumption of economic goods to consumption of ideological goods, and then tells us to create situations (guerrilla actions on many levels) that will break that pattern of socialized acceptance of the world as it is.”74

Historian Alice Echols argued that after 1975 cultural feminism eclipsed radical feminism, and fundamentally depoliticized it. She wrote, “Radical feminism was a political movement dedicated to eliminating the sex-class system, whereas cultural feminism was a countercultural movement aimed at reversing the cultural valuation of the male and the devaluation of the female.”75 Echols argued that feminists embraced cultural feminism because they could not deal with their differences in race, class, and sexuality, and it became easier to subsume them under universal ideals of womanhood. Anarcha-feminism embraced elements of cultural feminism, but rejected its apolitical aspects and the popular matriarchy theories pioneered by Elizabeth Gould Davis, Jane Alpert, Phyllis Chesler, and Mary Daly.76 These essentialist theories argued that the negative valuation of femininity rather than femininity itself should be challenged, and that power in the hands of women, rather than men, could lead to a feminist society. For example, Jane Alpert’s influential manifesto Mother Right argued that women’s potential for motherhood made them different from, but superior to, men.

Ehrlich critiqued “spirituality trippers” and the Amazon Nation for being out of touch with the reality of political and economic oppression, and for failing to recognize that all power, whether in the hands of women or men, is coercive, but other anarcha-feminists saw positive aspects of cultural feminism.77 Cathy Levine defended cultural projects and argued “creating a woman’s culture is the means through which we shall restore our lost humanity.”78 To Levine and other anarcha-feminists, notably Peggy Kornegger who crafted a theory of anarcha-feminist spirituality, anarcha-feminism embraced both the cultural and political. As many former feminists embraced spirituality gurus and their pacifying, depoliticizing, and anti-feminist programs, Kornegger argued that feminists must embrace both the feminist spirituality of theorists such as Mary Daly and physical and political resistance. Her 1976 article “The Spirituality Ripoff” in The Second Wave argued for a feminist approach to spirituality which emphasized both personal growth and political action. Kornegger wrote, “We need no longer separate being and action into two categories. It means that we need no longer call ourselves ‘cultural feminists’ or ‘political feminists’ but must see ourselves as both…. It means teaching ourselves womancraft and self-defense.”79 Describing this realization as a revolutionary “leap of consciousness,” Kornegger positioned anarcha-feminism as the next stage of consciousness raising which would mend the divides between spirituality and politics and between groups of feminists.

Anarcha-feminists combined aspects of radical, cultural, and socialist feminism, but added a critique of domination itself. Unlike socialist feminists they saw non-hierarchical structures as “essential to feminist practice.”80 Both radical and anarchist feminists dedicated themselves to building prefigurative institutions, a task socialist feminists did not always see as a vital part of their revolutionary program.81 While cultural feminists often rejected “male theory” and their roots in the New Left in favor of a de-politicized approach to feminism, anarcha-feminists combined emphasis on building a women’s culture with a strong theoretical perspective and class-consciousness. Constantly learning from other feminists and adjusting anarcha-feminist theory accordingly, rather than dogmatism, was a crucial feature of anarcha-feminism and part of the reason anarcha-feminists participated in such a variety of movements. Su Negrin wrote that “no political umbrella can cover all my needs” while Kornegger argued that it was crucial to break down barriers between feminists. As she wrote in 1976, “Although I call myself an anarcha-feminist, this definition can easily include socialism, communism, cultural feminism, lesbian separatism, or any of a dozen other political labels.”82 Anarcha-feminists learned from women in other parts of the feminist movement, despite their disagreements.

H. The Tyranny of Structurelessness or the Tyranny of Tyranny

The movement’s debate over structure and leadership gave the new anarcha-feminist position relevance and strategic value. An anarchistic commitment to equality and friendship structured feminist political organizations and fostered egalitarianism and respect, and reinforced mutual knowledge and trust, but when groups became clique-like and elites emerged, feminists utilized various structural methods to ensure equality.83 Radical feminist groups utilized lot systems to distribute tasks in an egalitarian manner, disc systems that ensured equal speaking time by distributing an equal amount of discs to members at the beginning of the meeting and instructing them to give one up each time they spoke, and collective decision-making through consensus or other means.84 They viewed women’s capacities as equal but stymied by their socialization, and empowered thousands of women to write, speak in public, talk to the press, chair a meeting, and make decisions for the first time.85

However, the goals of empowerment and egalitarianism came into conflict.86 “Elites”, or women with informal leadership positions within groups, often socially coerced other women into agreeing with them, or not stating their opinions at all, and in reaction the movement developed a paranoia about elites; women who exercised leadership or even attempted to teach skills to other members were often shunned and trashed.87 This triggered bitter statements like Anselma dell’Olio’s 1970 speech, “Divisiveness and Self-Destruction in the Women’s Movement: A Letter of Resignation” which claimed, “If you are…an achiever you are immediately labeled…a ruthless mercenary, out to get her fame and fortune over the dead bodies of selfless sisters who have buried their abilities and sacrificed their ambitions for the greater glory of Feminism.”88 Ironically, to some women, this justified the behavior of women who were in fact dominating others, and then presented themselves as tragic heroines destroyed by their envious and less talented “sisters.”89

In her widely read 1970 article, Jo Freeman, going by the pen name Joreen, argued that not only feminists’ personal practices, but the “tyranny of structurelessness” limited democracy and that to overcome it, groups needed to create explicit structures accountable to their membership.90 After circulating widely among feminists, the paper was published in the feminist journal The Second Wave in 1972. To Freeman, structure was inevitable because of individuals’ differing talents, predispositions, and backgrounds, but became pernicious when unacknowledged.91 Leaders were appointed as spokespeople by the media, and structurelessness often disguised informal, unacknowledged, and unaccountable leadership and hierarchies within groups. Thus, Freeman argued that structure would prevent elites from emerging and ensure democratic decision-making. Some anarcha-feminists, such as Carol Ehrlich agreed with this part of Freeman’s analysis while others, like Cathy Levine and Marian Leighton, opposed structure entirely.92 However, Joreen also decried the small group’s size and emphasis on consciousness raising as ineffective, and advocated for large organizations.93 Even after calling for “diffuse, flexible, open, and temporary” leadership, Freeman argued that to successfully fight patriarchy, the movement must move beyond the small groups of its consciousness raising phase and shift to large, usually hierarchical, organizations.94</div>

In her widely read 1970 article, Jo Freeman, going by the pen name Joreen, argued that not only feminists’ personal practices, but the “tyranny of structurelessness” limited democracy and that to overcome it, groups needed to create explicit structures accountable to their membership.90 After circulating widely among feminists, the paper was published in the feminist journal The Second Wave in 1972. To Freeman, structure was inevitable because of individuals’ differing talents, predispositions, and backgrounds, but became pernicious when unacknowledged.91 Leaders were appointed as spokespeople by the media, and structurelessness often disguised informal, unacknowledged, and unaccountable leadership and hierarchies within groups. Thus, Freeman argued that structure would prevent elites from emerging and ensure democratic decision-making. Some anarcha-feminists, such as Carol Ehrlich agreed with this part of Freeman’s analysis while others, like Cathy Levine and Marian Leighton, opposed structure entirely.92 However, Joreen also decried the small group’s size and emphasis on consciousness raising as ineffective, and advocated for large organizations.93 Even after calling for “diffuse, flexible, open, and temporary” leadership, Freeman argued that to successfully fight patriarchy, the movement must move beyond the small groups of its consciousness raising phase and shift to large, usually hierarchical, organizations.94</div>

Anarcha-Feminists asserted that the small group was not simply a reaction to male hierarchical organization, but a solution to the movement’s problems with both structure and leadership. In 1974, Cathy Levine, the cowriter of “Blood of the Flower,” wrote the anarcha-feminist response to Freeman, “The Tyranny of Tyranny.” Often printed with Freeman’s essay, Levine’s piece first appeared in the anarchist journal Black Rose.95 Levine argued that feminists who utilize the “movement building” strategies of the male Left forgot the importance of the personal as political, psychological oppression, and prefigurative politics. Instead of building large, alienating, and hierarchical organizations, feminists should continue to utilize small groups which “multiply the strength of each member” by developing their skills and relationships in a nurturing non-hierarchical environment.96 Building on the theories of Wilhelm Reich, she argued that psychological repression kept women from confronting capitalism and patriarchy, and thus caused the problem of elites.97 Developing small groups and a women’s culture would invigorate individual women and prevent burn out, but also create a prefigurative alternative to hierarchical organization. She wrote, “The reason for building a movement on a foundation of collectives is that we want to create a revolutionary culture consistent with our view of the new society; it is more than a reaction; the small group is a solution.”98

Similarly, Carol Ehlrich, Su Negrin, and Lynne Farrow argued that the small group allowed individuals to fight oppression in their everyday lives.99 All oppression involved individual actors, even if they acted as an agent of the state or the ruling class. Su Negrin, a member of Murray Bookchin’s Anarchos group and radical feminist, wrote and published Begin At Start in 1972.100 Negrin argued that the root structures of domination lie in everyday life because we are dominated but also dominate others, especially in sexual relationships and parenting, and applied this theory to her own life and relationships with her husband and children. These ideas reflected the feminist emphasis on the personal as political and pointing out domination in everyday life. Mutual trust in small groups helps people recognize and work with stylistic differences rather than trying to eliminate them. Similarly, Sue Katz, an anarchist lesbian leader of the working-class feminist Stick it in the Wall Motherfucker collective, responded to Rita Mae Brown’s calls for a lesbian party in a May 1972 issue of The Furies, claiming that small groups were actually efficient and could deal more effectively with internal problems.101 The small group emphasized the personal as political and developing relationships instead of the national campaign related strategy of liberal feminists and some socialist feminist groups.

Levine’s individualist focus starkly challenges the emphasis on conformity to ensure egalitarianism in many groups.102An anarcha-feminist understanding of equality, rather, would allow women to excel in different areas, provided they teach others the skills. Indeed, much anarcha-feminist work was educational and theorists like Kornegger focused on political education as a crucial area of tactics. As she argued in Anarchism: The Feminist Connection, women’s intuitive anarchism and egalitarianism was counteracted by socialization in an authoritarian society, but anarchist history and theory provided useful precedent for creating egalitarian structured organizations that also ensured leadership development and individual autonomy. Kornegger cited the example of the achievements of the anarchist organizations CNT-FAI and the collectives during the Spanish Civil War as an example of “the realization of basic human ideals: freedom, individual creativity, and collective cooperation.”103

Historically, anarchists grappled with the same questions of structure, organization, and prefiguration feminists were debating. These examples of political education and fluid structures that rotated tasks and leadership would help feminists watch for elites without resorting to voting or hierarchical models of organization.

I. No Gods, No Masters, No Nukes

As the anti-nuclear movement emerged and gained strength through the Seabrook nuclear power plant occupation, and later the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear meltdown incident, anarcha-feminists shifted their activity to large mixed-gender coalitions of affinity groups.104 Many anarcha-feminists who attended the 1978 Anarcha-Feminism: Growing Stronger conference sponsored by TIAMAT met up at the Seabrook anti-nuclear demonstrations, which attracted thousands to participate in non-violent civil disobedience to occupy the plant.105 Tellingly, when Tiamat eventually dissolved, members joined a women’s anti-nuclear affinity group, the Lesbian Alliance, and others worked with a mixed group on ecology issues.106Although they usually participated in women-only affinity groups, they interacted with men and authoritarian male politics in the larger movement. Anarcha-feminists also formed collectives in universities like Hunter College, Cornell, and Wesleyan.107 Often influenced by the writings of Murray Bookchin, who advocated political study groups, these affinity groups became the primary organizational model of the anti-nuclear direct action movement just as the similarly structured small group was the organizational model of the radical feminist movement.108

Throughout the 1980s, anarchist feminists connected the ideas they formed in the women’s liberation movement to an even wider range of issues, including violence against women, environmental destruction, militarism, and the nuclear arms race.109 Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz argues in the introduction to Quiet Rumors that the anarcha-feminist movement “had to all intents and purposes ceased to function” by 1980 as liberal feminists eclipsed radicals and male anarchists remained “traditional” in their sexism.110 However, even as anarcha-feminists shifted from focusing primarily on women’s oppression to a wider array of political issues, the organizational form and process, and the concern with both the personal and political remained. Consensus decision-making, a hallmark of prefigurative politics, was referred to as “feminist process” in the anti-nuclear movement, illustrating the influence of the many anarcha-feminist affinity groups and other feminists.111

However, it remains to be seen if replacing a separate women’s movement of small affinity groups with often mixed gender affinity groups was strategic. Today, many anarchist women and queer people, often in reaction to the sexism of anarchist men and rape culture inside anarchist collectives and movements, are forming their own affinity groups once again. It is worth investigating how changing ideas about gender and sexuality and the rise of queer and trans politics affected this change, and if it is a strategic one. How did theories of intersectionality and Black feminism interact with anarcha-feminism, and differ from earlier anarcha-feminist arguments that often did not directly address racial politics? The history of anarcha-feminism points to these and many more questions in an area of anarchist politics and theory that is generally under-investigated.

Conclusion

Often anarcha-feminists remarked that women were “natural anarchists” and positioned feminists as an untapped revolutionary force. However, neither the women’s movement nor the women in it always acted anarchistically. As activist Kytha Kurin wrote in 1980, “if anarchist tendencies within the feminist movement are accepted as a natural by-product of being female, it puts an unfair pressure on women to ‘live up to their natural anarchism’ and limits our potential for political development…. Many women’s groups do disintegrate, many women do exploit other women and men.”112 Radical feminists functioned as anarchists in anarchist spaces while lacking knowledge of anarchism. I think this proves the power of prefigurative politics and liberated anarchist spaces and organizations, free of the unnatural hierarchies that the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy forces upon us, to bring out the “intuitive anarchism” of a variety of people from white middle-class feminists to Occupy Wall Street protestors.113 Whether their relationships are based on sisterhood, ecology, or race or class solidarity, people have tried, and sometimes failed, to live without dominance and hierarchy. Once radical feminism was, as Kornegger wrote, “the connection that links anarchism to the future.”114 We must look for similar links in our movements today; we can see them throughout what anarchist scholar and activist Chris Dixon termed the anti-authoritarian current, from the prison abolition movement to the radical environmental movement to queer and feminist struggles today.115 If another world is possible, we can and must create it now.

Julia Tanenbaum is a student in the Philadelphia area involved with United Students Against Sweatshops and environmental organizing. She studies history hoping to help build our movements today.

Notes

- Peggy Kornegger, “Anarchism: The Feminist Connection,” in Reinventing Anarchy: What Are Anarchists Thinking These Days?, ed. Howard Ehrlich (Routledge and Kegan Paul Books, 1979). ↩

[2] Prefigurative politics is the desire is to embody within a movement’s political and social practices, the forms of social relations, decision-making, culture, and human experience that are the ultimate goal. Although anarcha-feminists did not use this language, various scholars have applied it to the women’s movement and the New Left. See Sheila Rowbotham, “The Women’s Movement and Organizing for Socialism,” in Beyond The Fragments: Feminism and the Making of Socialism, ed. Sheila Rowbotham, Lynne Segal, and Hilary Wainwright. (London: Merlin Press, 1979), 21-155, and Francesca Polletta, Freedom Is an Endless Meeting: Democracy in American Social Movements (Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2004). Anarcha-feminists frequently used language like “living the revolution” and “living out anarchism” to describe these practices. See Andrew Cornell, Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth Century (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016) on anarchist prefigurative politics during this period.

[3] Wini Breines, The Trouble between Us: An Uneasy History of White and Black Women in the Feminist Movement (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 92.

[4] Alice Echols, Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967-1975 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), 72.

[5] Sue Katz, “An Anarchist Plebe Fights Back,” The Furies 1, no. 4 (n.d.): 12. Rainbow History Online Archives.

[6] Breines, The Trouble Between Us, 90.

[7] It Ain’t Me Babe, December, 1, 1970, p.11. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

[8] Mary Daly, Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation (Beacon Press, 1973), 133.

[9] Polletta, Freedom Is an Endless Meeting, 162.

[10] Although today radical feminism is associated with trans exclusive feminists, during the 1970s it referred to a wider movement which asserted that gender, not class or race, was the primary contradiction and that all other forms of social domination originated with male supremacy. The “radical” served to differentiate it from liberal feminism, which focused solely on formal equality and ignored the fundamental problem of fighting for equality in an inherently unjust society. It also referred to the roots of radical feminists in the Marxist and sometimes anarchist New Left, where they experienced sexism that led them to reject the “male movement” and start their own, without the interference of their male oppressors. Radical feminists also differentiated themselves from “politicos,” women working in male dominated Leftist groups where the struggle against male supremacy was neglected. See Echols, Daring To Be Bad.

[11] “It Ain’t Me Babe – A Struggle for Identity,” It Ain’t Me Babe, June 8, 1970, 11. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

[12] Ellen Leo, “Power Trips,” It Ain’t Me Babe, September 17, 1970, 6. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

[13] Alix Kates Shulman, “Emma Goldman’s Feminism: A Reappraisal” in Shulman, ed., Red Emma Speaks: An Emma Goldman Reader (New York: Schocken Books, 1971), 4.

[14] Shulman, “Emma Goldman’s Feminism”, 6.

[15] Cathy Levine, “The Tyranny of Tyranny,” Black Rose 1 (1974): 56. Anarchy Archives.

[16] Emma Goldman Clinic, “Emma Goldman Clinic Mission Statement,” available at http://www.emmagoldman.com/about/mission.html (accessed July 9, 2015).

[17] “Emma Goldman” Off Our Backs. July 10, 1970, Wagner Labor Archives, New York University, 9, See also Candace Falk, Love, Anarchy, and Emma Goldman (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1984), and Kathy E. Ferguson, Emma Goldman Political Thinking in the Streets (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2011) for discussions of Goldman’s relationship with the feminist movement and working-class women’s movement

[18] Chicago Anarcho-Feminists, “Who We Are: The Anarcho-Feminist Manifesto,” Siren 1, no. 1 (April 1971). Anarchy Archives.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Arlene Meyers, “To Our Siren Subscribers,” Siren Journal, No. 1. Weber, “On the Edge of All Dichotomies: Anarch@-Feminist Thought, Process and Action, 1970-1983.,” 64. [21] “Black Cross Appears Again,” Siren Newsletter 1, no. 3 (1972): 2.; Siren 1, no. 4 (1972): 8. Anarchy Archives. [22] Eden W, “The Other Side of the Coin,” Siren Newsletter, no. 10 (1973). Anarchy Archives. [23] Ibid.

[24] How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004), 258.

[25] Susan Stryker, Transgender History (Berkeley: Seal Press, 2008), 105.

[26] Marie Leighton and Cathy Levine, “Blood of the Flower,” Siren, no. 8 (1973), 5. Anarchy Archives.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Marie Leighton, “Letter,” Anarcha-Feminist Notes 1, no. 2 (Spring 1977): 12. Anarchy Archives.

[30] Elaine Leeder, “The Makings of An Anarchist Feminist,” 1984, 2, Anarchy Archives.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Elaine Leeder, “Tiamat to Me,” Anarcho-Feminist Notes 1, no. 2 (March 20, 1977), 14, Anarchy Archives.

[34] Siren Newsletter, No. 2, and Siren Journal, No. 1. Slater, “Des Moines Women Form Support Group.” Anarchy Archives.

[35] Leeder, “Tiamat to Me.”

[36] Weber, “On the Edge of All Dichotomies,” 103.

[37] “Proposal to Merge the Anarcho-Feminist Network Notes and the Anarchist Feminist Communications Network,” Anarcho-Feminist Network Notes 1, no. 3 (October 1975): 9. Anarchy Archives.

[38] “Conference Flyer – Anarcha-Feminism: Growing Stronger” (TIAMAT Collective, June 9, 1978), Anarchy Archives.

[39] Leeder, “The Makings of An Anarchist Feminist.”

[40] Conference Flyer – Anarcha-Feminism: Growing Stronger” (TIAMAT Collective, June 9, 1978), Anarchy Archives.

[41] Barbara Ryan, Feminism and the Women’s Movement: Dynamics of Change in Social Movement Ideology, and Activism (New York, NY: Psychology Press, 1992), 54.

[42] Hellen Ellenbogen, “Feminism: The Anarchist Impulse Comes Alive,” in Emma’s Daughters (Unpublished, 1977), 6. Anarchy Archives.

[43] Ibid., 5.

[44] Evan Paxton, “Self Help Clinc Busted,” Siren, 1972, 8 edition, Anarchy Archives. Also see Sandra Morgen, Into Our Own Hands: The Women’s Health Movement in the United States, 1969-1990 (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 2002).

[45] Farrow, “Feminism as Anarchism,” 7. Also see Morgen, Into Our Own Hands.

[46] Ellenbogen, “Feminism: The Anarchist Impulse Comes Alive,” 7.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Kornegger, “Anarchism: The Feminist Connection.”

[49] Rebecca Staton, “Anarchism and Feminism,” Anarcho-Feminist Network Notes 1, no. 3 (October 1975): 6. Anarchy Archives.

[50] Judy Stein, Anarchist Feminist Notes 1, no. 1, 1976, 6 Anarchy Archives.

[51] Come! Unity Press, “Some Thoughts On Money and Women’s Culture,” 1976, Anarchy Archives.

[52] Peggy Kornegger, “Anarchism, Feminism, and Economics or: You Can’t Have Your Pie and Share It Too,” The Second Wave 4, no. 4 (Fall 1976): 4. Northeastern University Special Collections.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Mecca Reliance and Jean Horan, “Anarchist Conference April 19-21: Hunter College.” Off Our Backs, May 31, 1974. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University

[55] Ibid.

[56] Rosalyn Baxandall and Linda Gordon, Dear Sisters: Dispatches From The Women’s Liberation Movement (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2001), 12.

[57] Karen Johnson, “Mid West Conference,” Anarcho-Feminist Network Notes 1, no. 3 (October 1975): 5. Anarchy Archives.

[58] Marie Leighton, “Anarcho-Feminism and Louise Michel,” Black Rose 1, no. 1 (1974): 14.

[59] Karen Johnson, “Mid West Conference,” Anarcho-Feminist Network Notes 1, no. 3 (October 1975): 5. Anarchy Archives.

[60] Midge Slater, “Des Moines Women Form Support Group,” Anarchist Feminist Notes 1, no. 1 (1976): 10. Anarchy Archives.

[61] Grant Purdy, “Red Wing,” Anarcho-Feminist Notes 1, no. 2 (Spring 1977): 7. Anarchy Archives.

[62] Ibid. 8.

[63] Marie Leighton, “Anarcho-Feminism and Louise Michel,” Black Rose 1, no. 1 (1974): 8. Anarchy Archives.

[64] Lizzie Borden, “Women and Anarchy,” Heresies 1, no. 2 (1977): 74.

[65] Ehrlich, “Socialism, Anarchism, and Feminism,” 268.

[66] Leighton, “Anarcho-Feminism and Louise Michel,” 14.

[67] Ehrlich, “Socialism, Anarchism, and Feminism,” 26.

[68] Patrick Murfin, “International Working Women’s Day: Portrait of Penny Pixler, Feminist and Wobbly,” The Industrial Worker, March 8, 2015.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Ibid.

[71] On the CWLU’s split in 1976, see “The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union: An Introduction,” The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union Herstory Website, 2000. Some members angry at what they saw as the group’s white middle class orientation unleashed a scathing attack on the organization’s leadership at the 1976 International Women’s Day event which denounced feminism, lesbianism and the ERA. The CWLU split over how to deal with this situation and officially disbanded in 1977. Penny Pixler, “Notes From China,” Whirlwind 1, no. 11 (1978).

[72] Carol Ehrlich, “Socialism, Anarchism, and Feminism,” in Reinventing Anarchy: What Are Anarchists Thinking These Days?, ed. Howard Ehrlich (Routledge and Kegan Paul Books, 1977), 271.

[73] “Situationists – an Introduction,” Libcom.org, October 12, 2006 “Situationists – Reading Guide,” Libcom.org

[74] Ehrlich, “Socialism, Anarchism, and Feminism,” 271.

[75] Echols, Daring To Be Bad, 6.

[76] Ibid., 252.

[77] Ehrlich, “Socialism, Anarchism, and Feminism,” 260.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Peggy Kornegger, “The Spirituality Ripoff,” The Second Wave 4, no. 3 (Spring 1976): 18. Northeastern University Special Collections.

[80] Ehrlich, “Socialism, Anarchism, and Feminism,” 5.

[81] Ibid.

[82] Su Negrin, Begin at Start (Times Change Press, 1972), 128.; Kornegger, “Anarchism: The Feminist Connection.”

[83] Polletta, Freedom Is an Endless Meeting, 152.

[84] Ibid., 160.

[85] Baxandall and Gordon, Dear Sisters, 15.

[86] Polletta, Freedom Is an Endless Meeting, 169.

[87] Ibid., 152.

[88] Ehrlich, “Socialism, Anarchism, and Feminism.”

[89] Ibid.

[90] Jo Freeman, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” The Second Wave 2, no. 1 (1972).

[91] Ibid.

[92] Ehrlich, “Socialism, Anarchism, and Feminism,” 271.

[93] Freeman, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness.”

[94] Ibid.

[95] Cathy Levine, “The Tyranny of Tyranny” in Untying the Knot: Feminism, Anarchism, and Organization (Dark Star Press and Rebel Press, 1984).

[96] Levine, “The Tyranny of Tyranny,” 49.

[97] Ibid., 53.

[98] Ibid., 54.

[99] Ehrlich, “Socialism, Anarchism, and Feminism,” 271; Farrow, “Feminism as Anarchism.”

[100] Negrin, Begin at Start, 1.

[101] Sue Katz, “An Anarchist Plebe Fights Back,” The Furies 1, no. 4 (n.d.): 10.

[102] Polletta, Freedom Is an Endless Meeting, 170.

[103] Kornegger, “Anarchism: The Feminist Connection

[104] Barbara Epstein, Political Protest and Cultural Revolution: Nonviolent Direct Action in the 1970s and 1980s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991) 100.

[105] Elaine Leeder, “Feminism as Anarchist Process,” in Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-Feminist Reader, ed. Dark Star Collective, 2nd edition (Edinburgh: AK Press, 2008).

[106] Leeder, “The Makings of An Anarchist Feminist.”

[107] Weber, “On the Edge of All Dichotomies,”168.

[108] Epstein, Political Protest and Cultural Revolution, 55.

[109] Weber, “On the Edge of All Dichotomies,”133.

[110] Leeder, “Feminism as Anarchist Process,” 3.

[111] Epstein, Political Protest and Cultural Revolution, 159.

[112] Kytha Kurin, “Anarcha-Feminism: Why the Hyphen?” in Only a Beginning: An Anarchist Anthology, ed. Allan Antliff (Vancouver, BC.: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2004), 262. [113] Cindy Milstein, “‘Occupy Anarchism’: Musings on Prehistories, Present (Im)Perfects & Future (Im)Perfects,” in We Are Many: Reflections on Movement Strategy from Occupation to Liberation, ed. Kate Khatib, Margaret Killjoy, and Mike McGuire, (Oakland: AK Press, 2012). [114] Kornegger, “Anarchism: The Feminist Connection,” 248. [115] Chris Dixon, Another Politics: Talking Across Today’s Transformative Movements (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014).